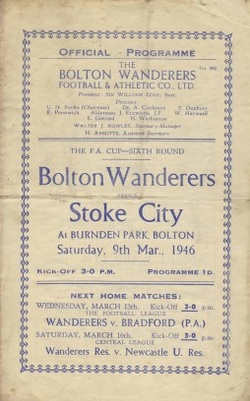

There was much more interest in the competition than just the locals, because this was the first post-war FA Cup competition which had been competed for. People also wanted the chance to see top players who were returning from the forces back to their clubs, Stokes’ Stanley Matthews being one of them.

Bolton fan’s would have been quite confident of progressing to the next round after winning the first leg 2-0 thanks to Ray Westwood scoring both goals.

An estimated crowd of over 85,000 people packed into the stadium. This being 20,000 over the official capacity and dwarfing the previous highest attendance of 43,000 that Burnden Park had seen that season.

The disaster happened at the Railway end of the ground, which was in a very poor state, like many other post-war grounds. There was just a bank of dirt and a few slabs of flag stones acting as steps.

The overcrowding was enhanced further due to part of the Burnden Road Stand having yet to re-open after the Ministry of Supply requisitioned it for use as storage during the War. In addition a set of turnstiles at the east end had been closed since 1940 meaning the crowd were all forced to enter the from one side of the embankment.

The turnstiles were closed 20 minutes prior to kick off, but by this point the stand was already overly full. 15,000 people were still outside many still managing to get in by climbing walls and entering a gate which had been left open by a father and son escaping the crush inside.

The game kicked off on schedule at 3PM, but minutes later it was halted as fans split onto the pitch. The pitch was cleared but two barriers gave way which caused the fans to surge forward again, crushing those underneath. Bill Cheeseman was at the game with his sister, who had wanted to see Stoke's Stanley Matthews. described how “All of a sudden those that were in front of us seemed to go – all falling down like a pack of cards. We managed to get out and I was glad about that."

Nat Lofthouse was by the referee when the official, George Dutton, was informed of the horrendous news of what was happening behind one of the goals. A police officer said “I Believe those people over there are dead” pointing to the bodies placed on the ground. After the referee called the two captains, Bolton’s Harry Hubbick and Stoke’s Neil Franklin, both teams were taken off the pitch and the field began to look like a military hospital where the dead and injured were laid on it.

After half an hour the unpopular decision to continue with the game was made by the then Chief Constable of Bolton, W J Howard. As the players were coming out with the bodies of the dead lying alongside the pitch covered with their coats, one of the spectators grabbed hold of a Stoke player and hurled abuse at him for continuing with the game.

A new sawdust lined touchline separated the players from the bodies. There was no half time interval, the sides simply changed ends presumably to get the game finished. The game finished 0-0.

Stanley Matthews described the events, “As we trotted on to the pitch I noticed the crowd was tightly packed, but this was nothing unusual at a big cup-tie. Our boys began well, and after ten minutes we had reason to feel confident as we were having the best of the game. It then happened! There was a terrific roar from the crowd, and I glanced over my shoulder to see thousands of fans coming from the terracing behind the far goal on to the pitch.”

A Home Office inquiry, chaired by Moelwyn Hughes, was launched to examine the events surrounding the disaster, but before the inquiry began the police, club officials and journalists were quick to pay the blame solely with the fans, stating holes had been torn in the fencing at the top of the embankment. Rowley stated, “Holes have been torn in the fencing at the top of the embankment in almost every conceivable place.” The Chief Constable alleged “There was no disorder … among those who gained entry in a legitimate manner. The trouble began when hundreds of people broke down the fences on the railway embankment.” He also said the police were “overwhelmed by the thousands of people rushing to the fence”.

The disaster brought about the Moelwyn Hughes report which recommended more rigorous control of crowd sizes. It also advised local authorities should inspect grounds with a capacity of 10,000 and safety limits should be in place for grounds holding 25,000 or more. Turnstiles should mechanically record spectator numbers and grounds should have their own internal telephone systems.

Immediately after the tragedy a Disaster Fund was set up by the Mayor of Bolton to help the families of the dead and injured. This raised £52,000 (about £2 million in today’s money), and was boosted by the proceeds from an international friendly between England and Scotland, playing out a 2-2 draw, at Maine Road on 24th August 1946, which sold out.

Bolton left Burnden Park in 1997 and Nat Lofthouse unveiled a memorial plaque in 2000 on the site of the old ground, which was now a supermarket. A plaque.

WILFRED ADDISON Moss Side, Manchester

WILFRED ALLISON (19) Leigh

FRED BATTERSBY (31) Atherton

JAMES BATTERSBY (33) Atherton

ROBERT BENTHAM (33) Atherton

HENRY BIMSON (59) Leigh

HENRY RATCLIFFE BIRTWISTLE (14) Blackburn

JOHN T. BLACKSHAW Rochdale

W. BRAIDWOOD (40) Hindley

FRED CAMPBELL (33) Bolton

FRED PRICE DEARDEN (67) Bolton

WILLIAM EVANS (33) Leigh

WINSTON FINCH Hazel Grove, Stockport

JOHN FLINDERS (32) Littleborough

ALBERT EDWARD HANRAHAN Winton, Eccles

EMILY HOSKINSON (40) Bolton

WILLIAM HUGHES (56) Poolstock, Wigan

FRANK JUBB Rochdale

JOHN LIVESEY (37) Bamber Bridge, Preston

JOHN THOMAS LUCAS (35) Leigh

HAROLD MCANDREW Wigan

WILLIAM MCKENZIE Bury

MORGAN MOONEY (32) Bolton

HARRY NEEDHAM (30) Bolton

DAVID PEARSON Rochdale

JOSEPH PLATT (43) Bolton

SIDNEY POTTER (36) Tyldesley

GRENVILLE ROBERTS Ashton-in-Makerfield

RICHARD ROBEY (35) Barnoldswick

THOMAS ROBEY (65) Billinge, Wigan

T. SMITH (65) Rochdale

WALTER WILMOT (31) Bolton

JAMES WILSON Higher Openshaw, Manchester.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed